by Diana Leafe Christian

Penny’s and my favorite conference presenter was Professor Yasuhiro Endoh of Aichi Sangyo University in Nagano. An older man in perhaps his early 60s with an amiable expression and an unmistakable air of warmth and friendliness, Professor Endoh travels the length of Japan advocating “collective housing” through his nonprofit, “Team of Green Growth.” He showed slides of a successful 22-year-old collective housing development in Kyoto, “U Court.” The project, completed in 1985, consists of 48 units in three buildings of from three to five stories each. The buildings are arranged around a south-facing “U”-shaped courtyard surrounding tall trees and a patio. U-Court doesn’t have a common kitchen/dining room. However, with a shared meeting hall, all stairwell entries facing into the courtyard so people meet their neighbors daily, open and shared ivy-covered balconies that serve as outdoor hallways running along the courtyard side of the buildings, and parking out of sight in one corner of the property, it sure seemed like “proto-cohousing” to me.

Professor Endoh emphasized the importance of trees and the natural environment in creating community. U-Court residents debated whether to plant trees in their central courtyard, which would have been expensive for them, but finally did plant trees. The presence of these trees later made all the difference in cooling the building, adding a beautiful, shady outdoor place for neighbors to gather in spontaneous as well as planned meetings, picnics, and celebrations. U-Court residents also all grew ivy up the sides of the buildings and especially across their shared balconies. At first they couldn’t get flowers and shrubs started along courtyard walkways because their toddlers would gleefully rip them out. So U-Court parents waited until the children were slightly older and asked them to plant flowers and shrubs and water them. The kids leapt into the project and proudly cared for the landscaping for years, later noting how important it had been to them return from school everyday and feel welcomed home by natural beauty. The parents also considered building a small round pond for the children to wade and splash in. While some were concerned it would be unsafe, they finally did build a pond, and it became the centerpiece of the children’s experience of the courtyard as they grew up. “You can’t believe the happy memories people who’d grown up at U Court had when they came home from school only to find that one of the men had gotten drunk and fallen into the pond again,” Professor Endoh explained, showing a photo of a man half-lying in a shallow pool, submerged up to his armpits, a silly grin on his face. Nature, ponds, and water are so important to Japanese people that one pair of neighbors created a small fishpond on their shared balcony and stocked it with koi.

Professor Endoh’s longitudinal study of the of young adults who’d grown up at U-Court indicated that they had loved the natural environment there and their sense of safety and connection to so many adults who served as substitute aunties and uncles. Like kids raised in community anywhere, they were much more confident and socially developed than their counterparts who’d grown up in conventional housing. And, not surprisingly, they wanted to move back to U-Court to raise their own children there too.

by Diana Leafe Christian (for Cohousing Journal online, February, 2008)

After the Japanese Ecovillage Conference in Tokyo in late November, 2007, I and one the conference hosts, Akemi Miyauchi, visited three “collective housing” projects in Tokyo. At the conference I first heard this term for high-density housing projects with various kinds of common space—but it sure sounded like cohousing to me!

A few days after touring Kankanmori no Kaze Cohousing (See Part I in the February, 2008 issue), Akemi and I visited developer Tetsuro Kai, who at the ecovillage conference had described three beautifully designed and landscaped “collective housing” projects. We met in his offices at one of his projects: the 12-unit Kyodo no Mori (“Forest of Kyodo”) in the Setagawa district of Tokyo. Kyodo no Mori is three-story building on a tiny, fifth-acre lot, with vine-covered balconies, passive solar heating and cooling, solar-powered water pumping, and a constructed wetlands for greywater treatment on a rooftop terrace. Units average at about 970 sq. ft. Unlike Kankanmori, most units are not rented but owned by Kyodo no Mori’s residents. Common house features were not included in the building, however residents have shared outdoor space in a ground-floor courtyard, small second-floor terrace, and rooftop garden, which has a small barbeque grill surrounded by built-in seating for cook-outs. Completed in 2000, this project was described as Japan’s first cohousing community in Graham Meltzer’s 2005 book, Sustainable Communities.

Mr. Kai, a charming and gracious host, seemed inspired and passionate about his collective housing projects, and the participatory design process he developed for them. He and the architect met with future residents of Kyodo no Mori to learn what they’d ideally like in their individual apartments. He and the architect met first with individual households, then in small groups of several households, and lastly as a whole group. A problem for concern for any one household was considered an issue for the whole community, and solutions were applied to all residences. Mr. Kai realized that this process would not only help the project to better serve the needs of its future residents, but would also help create a sense of community before everyone moved in. Although similar to the participatory process used by the Danish architects who developed cohousing in the 1960s, Mr. Kai’s method is not based on the cohousing process and was created independently.

Mr. Kai also told us about the 15-unit Keyaki House project, completed in 2003, which we were about to see. The original owner of the __-acre property had a one-story traditional Japanese house and a relatively large garden. To reduce future inheritance taxes for his heirs, the owner sold part of the property to Mr. Kai for high-density housing development. Because Tokyo needs more housing, they reward urban landowners who sell their property for this purpose with inheritance tax breaks. The owner didn’t want to leave the site and so built a new two-story house for himself on the part of the property he retained. Mr. Kai suggested a win-win arrangement in which his traditional one-story house became the meeting hall and common space for Keyaki House residents and himself, who together form a small community. Everyone shares the garden courtyard formed between the three buildings.

The owner’s favorite tree, which he had climbed as a boy, is an 80-foot Japanese Zelkova tree (Keyaki in Japanese). But it was in the wrong location for the site plan to work, so Mr. Kai’s company dug up the huge tree and moved it 30 feet!

We saw a scale model of Mr. Kai’s newest project, Kaze no Mori (“Wind in the Forest”), which has the same kind of site-use arrangement as Keyaki House with the original property owner. Like Kyodo no Mori, most residents of Kaze no Mori and Keyaki House had input into the design of their units via the participatory design process, and meet regularly to make community decisions.

When we arrived at Keyaki House, a short distance away, we saw the magnificent Keyaki tree, with a trunk diameter of about three feet. It was truly the centerpiece of the courtyard, nestled in the inner corner of the L-shaped building, with a network of lacy-looking open-mesh metal stairways and walkways curving around it. Next to the base of the Keyaki tree and under the overhead walkways was an enchanting sight—a Japanese-style fishpond with large stepping stones leading across to the stairway and elevator leading to the apartments above. Before you encounter concrete, metal, and high-technology, you move through a beautiful natural environment. On the second floor landing Mr. Kai pointed out how moveable screens of closely spaced wooden lattice strips on the outside “wall” of each unit’s wide balcony create a privacy gradient between each apartment and the wide curving metal walkways, which also serve as common space. We saw the rooftop vegetable garden on the four-story wing, and the tiny grassy park on the roof of the five-story wing, where in summer community children sometimes put up tents and camp out.

The traditional Japanese love of nature, gardens, and especially forests and trees, was quite evident in the projects I visited as well as in similar projects described at the conference. I saw this only in their vine-covered trellised balconies and tree-filled courtyards, but also in evocative names such as “and “Forest of Kyodo” and “Wind in the Forest. (And the name of the cohousing project we’d visited earlier, Kankanmori no Kaze, means “Winds of Kankanmori Forest.” )

What the projects I visited have in common are residents who had input into the design, hold community meetings, and live in projects in which the site plan and shared common space help induce a sense of community. However, Kankanmori has the same kinds of common house amenities as you’ll find in any cohousing community in North America, but the other projects have minimal common space. And perhaps because Kankanmori has slightly smaller units and looked like any concrete high-rise anywhere, it seemed more affordable. Mr. Kai’s three projects seemed more upscale because of the somewhat larger units and the level of beauty and attention to detail in design and landscaping.

While Japanese people seem to love using English terms for concepts arising in the West (like “bioregional” and “ecovillage”), I wondered why the term for these communities in Japanese is “collective housing” rather than the English word “cohousing.” However, Hiroko Kimura, founder of Kankanmori, did describe the project as “Tokyo Cohousing” when she presented at the first Japanese Ecovillage Conference in 2006.

Also, while in any cohousing community tour in North America people are routinely invited into homes to see the interiors of a typical units, I got the impression that this will not happen in Japan because of significant cultural differences—the important distinction made between the “public face” and “private face” in Japan, and the fact that in Japan one’s home is an exceptionally private place. Hence, as gracious as our hosts were, we were shown only the courtyard and rooftops of Keyaki House, the courtyard and Mr. Kai’s offices at Kyodo no Mori, and the interior common spaces and rooftop terraces at Kankanmori.

Given the tendency in Japan to adopt and master useful innovations, I wouldn’t be surprised if cohousing takes off in a big way in this country. Perhaps in the not-too-distant future we’ll be meeting at an international cohousing conference . . . in Kyoto!

Diana Leafe Christian is editor of a free online ecovillage newsletter, “Ecovillages and Sustainable Communities.” (Diana@ic.org). Author of Finding Community: How to Join an Ecovillage or Intentional Community, and Creating a Life Together: Practical Tools to Grow Ecovillages and Intentional Communities, she was editor of Communities magazine for 14 years. Diana lives at Earthaven Ecovillage in North Carolina. www.DianaLeafeChristian.org

DianaLeafeChristian.org

by Diana Leafe Christian (for Cohousing Journal online, February, 2008)

As cohousing is increasingly becoming a global phenomenon, I’ve become curious to learn how different countries mold the concept to reflect their cultural, financial, and regulatory realities. I learned that firsthand after I had a chance to see three cohousing projects in Japan recently.

After the Japanese Ecovillage Conference in Tokyo in late November, 2007, three of us visited the 28-unit Kankanmori no Kaze Cohousing project in Tokyo. My two friends were Giovanni Ciarlo from Huehuecoyotl Ecovillage in Mexico, and Akemi Miyauchi, one of our wonderful conference hosts. Giovanni and I had given presentations about intentional communities at the conference, and we were eager to see similar projects in Japan. There appear to be relatively few intentional communities in that island nation, and perhaps only four cohousing communities so far—depending on how one defines the term.

We first learned of Kankanmori at the conference through presentations on what the Japanese call “collective housing” in Sweden, Denmark, the US, and Japan. I was quite surprised to learn that the first example one conference presenter could find of collective housing in modern times was in Sweden before World War II, where single mothers organized shared apartment buildings with common kitchen/dining rooms and shared childcare.

Kankanmori no Kaze (which means “The Winds of Kankanmori Forest”) is located in the 12-story Nippori Community House in the Arakawa section of Tokyo. The second and third floors contain the apartment units, common spaces, and rooftop terraces of the multi-generational Kankanmori Cohousing. However, the other floors are not part of the cohousing project: the ground floor is a restaurant, a nursery school, and a medical services station staffed by nurses for residents and neighbors, the higher floors contain a nursing home and independent-living apartments for mobile seniors, and the top floor offers furo bath facilities all residents can use.

Kankanmori differs from most cohousing projects in the West in that it is entirely rental units. The studio and two-bedroom units (no one-bedroom units), which range from 270 to 645 sq. feet, rent for between approximately $640 to $1550 a month, plus about $65 a month for each unit’s share of utilities for the common spaces. The Kankanmori project was considered quite an experiment, as its future residents gave their input into the design, and provide the cleaning and maintenance of the common spaces—unusual for Japan.

Giovanni, Akemi, and I entered Kankanmori through an outdoor stairway to the second floor entrance, where we met architect and project founder Hiroko Kimura, who gave us a tour of the common facilities. On the first cohousing floor we saw the common kitchen and pantry, which looked like every common house kitchen I’ve ever seen but for the row of rice cookers, a bamboo vegetable steamer, and Japanese rather than English on the labels of every package, bottle, and can. We toured the spacious dining room, the small living room off the dining room, and the outdoor dining terrace with a living “wall” of trellised vines on the balcony. We visited the children’s play area, bathroom, laundry and ironing rooms, the indoor/outdoor woodworking/crafts terrace, and the flower garden and vegetable garden terraces. Located on the roof of the first floor, the gardens had deep raised garden beds in wooden frames, wooden walkways, and rows of plastic compost bins. On the next floor of the cohousing complex we saw the group’s office, library shelves, woodworking shop, and guest room.

Located on the roof, the flower garden and vegetable garden terraces had deep raised beds in wooden frames, wooden walkways and rows of plastic compost bins. The Japanese had an ancient, even sacred, sense of connection to nature, especially trees and forests. (They’ve preserved 66% of their island nation in forest, which is impressive, given the pressure to cut forests to get more arable land to feed a population of 127 million.) But nowadays most Japanese in urban areas live in small box-like apartments in concrete high-rises, with little connection to neighbors or nature. Land is so expensive that few housing developers include gardens or landscaping. So Kankanmori’s connection to neighbors and to nature once again is quite exceptional.

Ms. Kimura also showed us the community’s bulletin-board systems for cooking and cleaning schedules and using the laundry facilities, and described how they worked. People write their names on small brightly colored circular magnets, which they place on a large wall calendar on the dates on which they’d like to cook and clean. In the laundry room they affix small paper tags to their washer or dryer they’re using to let the next person know how to dry their wet loads or where to put their dried loads before they put in their own. Ms. Kimura also described community meetings, and told us that when residents have differences, “We just talk together until we can come to agreement about what to do.”

The most moving part of the tour, for me, was that while I was 5,000 miles from North America, visiting a culture significantly different from my own, the common spaces and description of Kankanmori’s cooking rotation, laundry use, and interpersonal process were so familiar. Giovanni and I told Ms. Kimura that the kinds of conflicts and topics she described in their meetings also came up at Huehuecoyotl and Earthaven as well. Whether in Mexico, Japan, or North Carolina, communitarians seem to evoke the same set of living-together issues!

Before we left Kankanmori, Ms. Kimura invited us to participate in one of their common meals the next time we came to Tokyo. We said we’d love to!

Part II will examine two additional high-density housing projects in Tokyo that combine individual units with unusual methods for creating common space.

Diana Leafe Christian is editor of a free online ecovillage newsletter, “Ecovillages and Sustainable Communities.” (Diana@ic.org).

Author of Finding Community: How to Join an Ecovillage or Intentional Community, and Creating a Life Together: Practical Tools to Grow Ecovillages and Intentional Communities, she was editor of Communities magazine for 14 years.

Diana lives at Earthaven Ecovillage in North Carolina.

DianaLeafeChristian.org

By Giovanni Ciarlo, Diana Leafe Christian

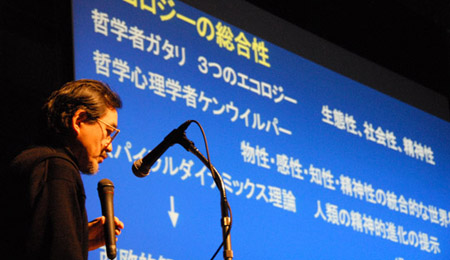

The 2007 International Ecovillage Conference was held in Tokyo, Japan, November 23-24, 2007 with a packed crowd of Japanese environmental activists, progressive university professors, enthusiastic students, and the “green press” in Japan. The second such event held in Tokyo, the conference was hosted by BeGood Cafe and the Permaculture Center of Japan, two nonprofits dedicated to promoting ecological sustainability throughout the country.

The conference was kicked off by Koji Itonaga, Professor of Biosource Sciences at Nihon University and conference co-host, who urged Japan, among other tasks, to protect and revitalize its remaining 135,000 villages through permaculture design and ecovillage projects, ecologically sustainable housing, bioregionalism, and eco-tourism. Yasuhiro Endo, Professor at Aichi Sangyo University, called for more collective housing projects in Japanese cities, showcasing the very successful “U-Court” collective housing project in Kyoto, to much laughter and applause. Ms. Ikuko Koyabe, Professor at Japan Women’s University and author of Let’s Live in a Collective House, presented case studies of collective houses in Sweden, Denmark, and the US, and how this has been translated to collective housing in Japan, especially in the Kankanmori collective housing project in Tokyo. Other Japanese presenters described collective housing communities in Tokyo, ecovillages in Denmark, a Japanese aid project providing wind generators to communities in East Africa, sustainable forestry and building with wood products to create better home environments and revive the economy of Japan’s mountain villages, and plans to revitalize Japanese villages in the Goshima Islands and Hokkaido Date city, respectively.

Overseas guests presented as well. Diana Leafe Christian, author of Finding Community and Creating a Life Together, former editor of Communities magazine, and editor of the new online ecovillage newsletter, Ecovillages and Sustainable Communities, introduced the ecovillage concept with examples worldwide. In a second presentation she focused specifically on the ecologically and financially sustainable aspects of three projects: Earthaven in North Carolina (where she lives), Findhorn Foundation in Scotland, and Kommune Niederkaufungen in Germany.

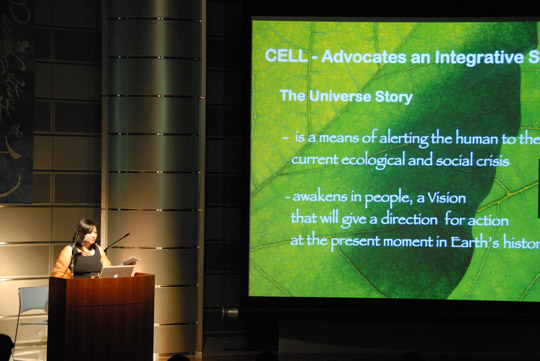

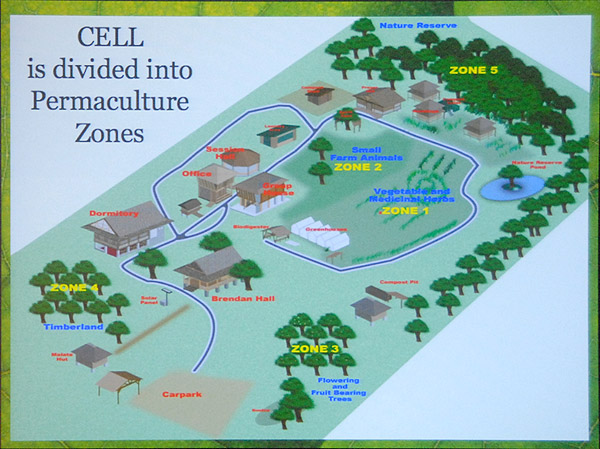

Environmental scholar Penny Velasco, director of the GEN-Oceania/Asia in the Philippines, directing manager of Earth Day in the Philippines, and author of Are You the Forest King?, described how a new ecovillage project, Pintig Cabio in Manila, is being cofounded by three nonprofits: Happy Earth, which produces environmental education materials; The Center for Ecozoic Living and Learning (CELL), a Creation Spirituality-oriented environmental education center; and the Cabiokid Foundation, a fully developed permaculture demonstration site immediately adjacent to the ecovillage site. Giovanni Ciarlo, cofounder of Huehuecoyotl

Ecovillage in Mexico, representative from Mexico to the Ecovillage Network of the Americas (ENA), and member of the Board of Directors of the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN), gave a presentation about ecovillage projects in Latin America, including

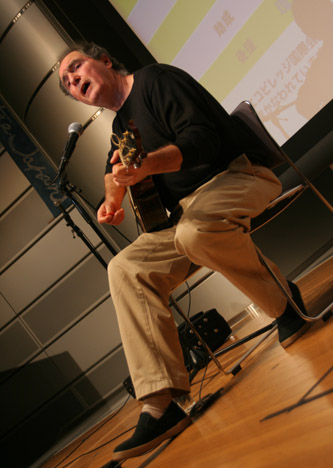

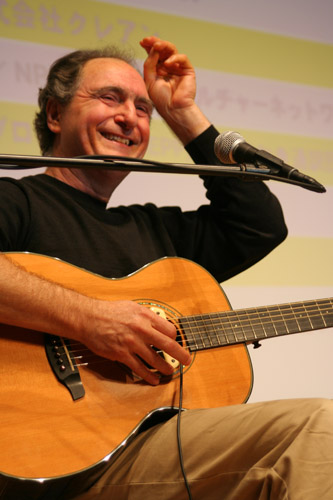

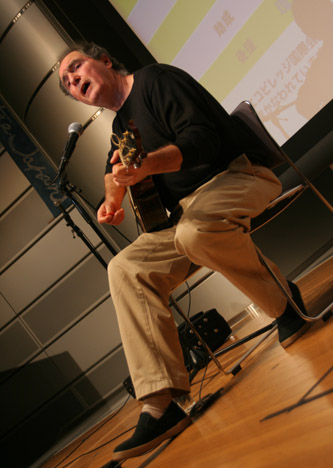

Huehuecoyotl and Las Cañadas in Mexico, Sasardí Nature Reserve in Colombia, IPEC and ABRA 144 in Brazil. Giovanni also played guitar and sang, getting the crowd clapping and singing along to songs, including his original songs, in Spanish. Kyle Holtzetar, an American Ph.D. student at Nihon University, described the ecologically sustainable aspects of Camphill Kimberton Hills community in the U.S.

The ecovillage conference was also blessed by an unexpected visit by renowned sustainability activist Helena Norberg-Hodge. Founder and director of the International Society for Ecology and Culture, co-founder of the International Forum on Globalization, director of the Ladakh Project, author of Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh,

recipient of the Right Livelihood Award, and longtime GEN activist, Helena, in Japan on other business, stopped by the ecovillage conference to help encourage ecovillage activism in Japan. She also described her new video project about measuring a country’s progress in terms of its happiness levels.

Professor Yasuhiro Endoh of Aichi Sangyo University in Nagano showed slides of U- Court, a successful 22-year-old collective housing development in Kyoto. The project, completed in 1985, consists of 48 units in three buildings, each three to five stories tall. The buildings are arranged around a south-facing U-shaped courtyard containing tall trees and a patio. U-Court doesn’t have a common kitchen or dining room, but in many ways it resembled cohousing. It boasts a shared meeting hall, stairwell entries that face into the courtyard, shared ivy-covered balconies running like outdoor hallways along the courtyard sides of the buildings, and hidden parking in one corner of the property.

At the end of each day the presenters took part in a panel discussion moderated by Koji Itonaga, Professor in the College of Bioresource Science at Nihon University.

The conference was widely reported on through print media by Bio-City magazine editor Hiroki Sugita as well as by Yukihiro Noda of the The conference was widely reported on through print media by Bio-City magazine editor Hiroki Sugita as well as by Yukihiro Noda of the television program “Green-Power TV,” who will post a video of interviews and conference highlights in January at www.green-power.tv

Official conference sponsors included Bio City magazine, several Japanese sustainability-oriented corporations, and the Japanese Ministries of the Environment and of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. Emcees were Jun Shikata of BeGood Cafe and Koji Itonaga.

The first International Ecovillage Conference in Japan was held in October, 2006 in Tokyo. Overseas guests were Lois Arkin of Los Angeles Eco-Village and West US representative to ENA, Liz Walker of EcoVillage at Ithaca in New York state and co-creator of GEN’s EDE program, Max Lindegger of Crystal Waters in Australia and director of GEN-Oceania/Asia, and Marti Mueller of Auroville community in India.

CONTACT:

BeGood Cafe: begoodcafe.com, Contact Form

Diana Leafe Christian: DianaLeafeChristian.org, diana@ic.org

Penny Velasco: happyearth.info, penny@happyearth.info

ena.ecovillage.org

gen.ecovillage.org

Giovanni Ciarlo: sircoyote@aol.com

– Ecovillage Network: http://www.ecovillage.org

– Ecoaldea Huehuecoyotl: http://www.huehuecoyotl.net

By Diana Leafe Christian

The Japanese audience was singing along with ecovillager Giovanni Ciarlo—in Spanish! It was the second International Ecovillage Conference, held in Tokyo in November 2007. The packed crowd included environmental activists, progressive university professors and students, and Japan’s “green press.” Speakers included professors of architecture and engineering, innovative housing developers, environmental activists with special projects in rural areas of Japan, and three overseas guests—Giovanni, Penny Velasco, and me.

The conference was a wonderful opportunity for the three of us to learn about Japanese culture. We were told that people in Japan once had a powerfully developed sense of community and connection to neighbors, in thousands of rural villages as well as in city neighborhoods. They also had an ancient, sacred sense of connection to nature, especially trees and forests. But nowadays most Japanese in urban areas live in tiny apartments in concrete high-rises, with little connection to neighbors or nature. Land is so expensive that few apartments include gardens or landscaping. So the Japanese projects presented at the conference, while not “ecovillages” perse, were nevertheless inspiring to the audience because they made the connection with neighbors and nature once again.

They were inspiring to us overseas guests, as well—we enjoyed learning about Japanese colleagues doing projects similar to our own. For instance, Ikuko Koyabe, architect and Professor at Japan Women’s University, presented case studies of what the Japanese call “collective housing”—what we would call cohousing. She described projects in Sweden, Denmark, and the US, and then introduced us to the Kankanmori cohousing project in Tokyo.

Housing developer Akinori Sagane spoke of his work supporting the economic revitalization of remote mountain villages by encouraging sustainable forestry practices and a return to using wood as a building material.

Professor Yasuhiro Endoh of Aichi Sangyo University in Nagano showed slides of U- Court, a successful 22-year-old collective housing development in Kyoto. The project, completed in 1985, consists of 48 units in three buildings, each three to five stories tall. The buildings are arranged around a south-facing U-shaped courtyard containing tall trees and a patio. U-Court doesn’t have a common kitchen or dining room, but in many ways it resembled cohousing. It boasts a shared meeting hall, stairwell entries that face into the courtyard, shared ivy-covered balconies running like outdoor hallways along the courtyard sides of the buildings, and hidden parking in one corner of the property.

Housing developer Tetsuro Kai showed slides of two collective housing projects in Tokyo: Kyodo no Mori and Keyaki House. Each is a concrete multi-story apartment building with rooftop gardens and vine-covered vertical surfaces and balconies. The three-story Kyodo no Mori features passive solar heating and cooling, a rooftop wetlands for greywater recycling, and a solar-powered water pump. It was described as Japan’s first cohousing community in Graham Meltzer’s 2005 book, Sustainable Communities (and in the Winter 2005 issue of Communities magazine). Keyaki House is a five-story building whose residents use the original traditional house on the property as their shared common space and meeting room.

Other presenters described ecovillages in Denmark, a Japanese aid project providing wind generators to communities in East Africa, Camphill Kimberton Hills in the US, and plans to revitalize Japanese villages in the Goshima Islands and the city of Hokkaido-Date.

Giovanni, a cofounder of Huehuecoyotl Ecovillage, is Mexico’s representative to the Ecovillage Network of the Americas and a Board member of the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN). His first presentation at the conference was a slide show about successful up-and-running ecovillages in Latin America, including Huehuecoyotl and Las Cañadas in Mexico, Sasardí Nature Reserve in Colombia, and ABRA 144 in Brazil. When he played guitar and sang some of his original songs, he had everyone tapping their feet and moving to the music.

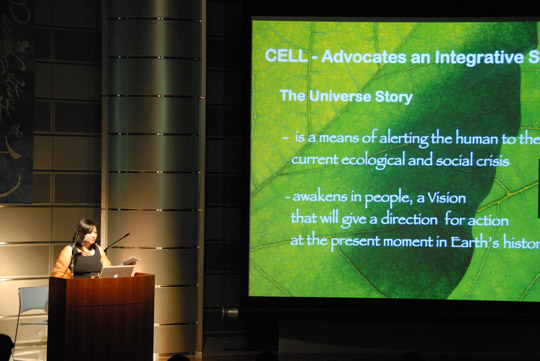

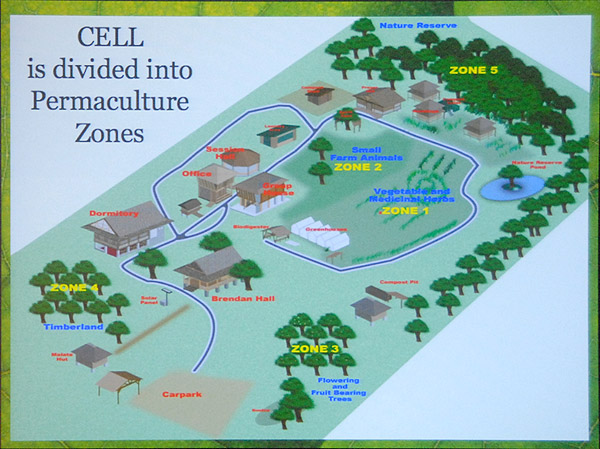

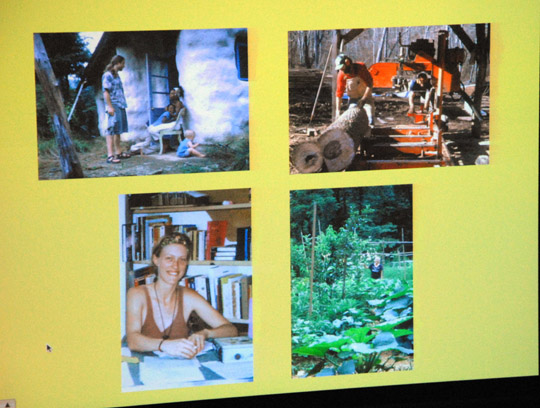

Environmental scholar Penny Velasco is director of GEN-Oceania/Asia in the Philippines and director of Happy Earth, a nonprofit that produces environmental education materials. She showed slides of Pintig Cabiao, the ecovillage she is helping to start in Manila. Pintig Cabiao is being cofounded by three Filipino nonprofits: Happy Earth; the Center for Ecozoic Living and Learning, a Creation spirituality-oriented environmental education center; and the Cabiokid Foundation, a fully developed permaculture demonstration site adjacent to the planned ecovillage site.

I gave an overview of the concept of ecovillages, with statistics from GEN, quotes from well-known ecovillage activists, and photos of Damanhur in Italy, Tlholego in South Africa, IPEC in Brazil, and Auroville in India. My second presentation focused on ecological and financial sustainability in ecovillages, highlighting Findhorn Foundation in Scotland, Kommune Niederkaufungen in Germany, and Earthaven in North Carolina, where I live.

The conference was hosted by BeGood Cafe and the Permaculture Center of Japan, two nonprofits dedicated to promoting ecological sustainability. Sponsors also included the Tokyo-based Bio City magazine, several Japanese sustainability-oriented companies, and the Japanese Ministries of the Environment and of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. On-stage hosts were Jun Shikita of BeGood Cafe and Koji Itonaga of the Permaculture Center of Japan and the College of Bioresource Sciences at Nihon University.

Giovanni, Penny, and I grew very fond of the folks at BeGood Cafe, who hosted us royally with Japanese dinners every night. The organization’s founder and director, Jun Shikita, is a former fashion industry executive who started the cafe in 1999 to share and promote practical environmental information. We were also impressed by Akemi Miyauchi, the ever-helpful, untiring coordinator, who took care of everything we needed.

After the conference the BeGood Cafe folks helped us foreign guests visit several Japanese intentional communities—a wonderful treat. Penny traveled to the Konohana Family, a 14-year-old organic farming community near Mt. Fuji. The goal of this vegetarian community, which produces nearly all its own food, is to live in harmony with the Earth and with each other. “You could feel the love among the members there,” Penny later told us.

Giovanni, Akemi, and I visited Kankanmori Cohousing in Tokyo, which is located on the second and third floors of a 12-story apartment building. We were given a tour of the common facilities by the project’s architect and founder, Ms. Hiroko Kimura. Even though we were in a culture quite different from ours, Kankanmori felt familiar—especially its common kitchen and other shared facilities, and our guide’s description of the cooking teams, common laundry use, and interpersonal process in meetings. Giovanni and I told Ms. Kimura that the kinds of topics she described in their meetings came up at Huehuecoyotl and Earthaven as well. Whether in Mexico, Japan, or North Carolina, communitarians seem to face the same kinds of issues.

Akemi and I also briefly visited Tetsuro Kai and his two beautifully designed and landscaped collective housing projects, Kyodo no Mori and Keyaki House.

I believe we in the communities movement can learn much from our Japanese colleagues—architects, developers, professors, and environmental activists like the folks at BeGood Cafe. It was an honor to meet them.

Diana Leafe Christian, author of Finding Community and Creating a Life Together and former editor of Communities magazine, is editor of the new online ecovillage newsletter, “Ecovillages and Sustainable Communities.” She lives at Earthaven Ecovillage in the US.

Contact info:

Diana Leafe Christian: dianaleafechristian.org; diana@ic.org

BeGood Cafe: begoodcafe.com/archive-bgc/main/archives/ecvc2007_report (in Japanese, with photos); Contact Form

Giovanni Ciarlo and Huehuecoyotl Ecovillage: huehuecoyotl.net; sircoyote@aol.com

Penny Velasco: happyearth.info; penny@happyearth.info