>> 3日間大盛況で終了しました!第3回エコビレッジ国際会議 レポートはこちら

>> 3日間大盛況で終了しました!第3回エコビレッジ国際会議 レポートはこちら

3日間で53プログラム!笑顔がつながる暮らし方の祭典

世界のエコビレッジムーブメントの火付け役を始め、アジアのキーパーソン、日本各地の実践者など、総勢50名以上のゲストが集結します!

レクチャー、ディスカッション、ワークショップ、ライブ、上映会、交流カフェなど、つながりを紡ぐ仕掛けが盛りだくさん。ラクして楽しみながら、「自分にできること」「豊かな暮らし」を始めた仲間がこんなにたくさんいます。希望とエネルギーをもらいに、ぜひ会場に遊びに来てください。!

イベント概要 / プログラム / ゲストプロフィール / チケット情報 / お問合せ / ボランティア情報 / ご協賛企業ページ/ 応援メッセージ/ Q&A/ 寄付のお願い/ English

※チラシのダウンロードはこちら→ PDF | jpg表 | jpg裏

■プログラム

3日間通して合計53のプログラムを開催予定!

タイムテーブルやプログラム概要、ゲスト情報が満載のプログラムガイドを公開中!

下記よりダウンロードしてください→ PDF(4月15日更新)

■イベント概要

| 日時: |

2009年4月24日(金)~26日(日) |

| 場所: |

東京ウィメンズプラザ(ホール、視聴覚室、第1会議室)、国連大学(エリザベスローズホール、レセプションホール)、地球環境パートナーシッププラザ |

| 主催: |

NPO法人ビーグッドカフェ |

| 共催: |

NPO法人パーマカルチャー・センター・ジャパン |

| 協力: |

日本エコビレッジ推進プロジェクト、懐かしい未来ネットワーク、株式会社ビオシティ、Global Ecovillage Network、株式会社オルタナ、greenz.jp(株式会社ビオピオ)、国境なき通訳団、地球環境パートナーシッププラザ 他 |

| 協賛: |

東京建物株式会社、エコプロダクツ2009、株式会社野毛印刷社、アミタ株式会社、株式会社地球の芽 |

| 後援予定: |

環境省、国土交通省、国連人間居住計画、国連訓練調査研究所、日本大学生物資源科学部、21世紀社会デザイン研究学会、デンマーク大使館、福島県飯舘村、毎日新聞社 |

プログラム概要:

- 国内外のゲスト~先駆者に聞く世界・アジア・日本の最新動向!

- 国内のエコビレッジ実践者による報告~いよいよ始まった日本型エコビレッジ!

- 西欧型/アジア型/日本型、都会型/田舎型など、多彩なエコビレッジ関係者を交えてのパネルディスカッション

- 「農業」「教育」「地域再生」「事業/起業」「アート」などエコビレッジの各要素を掘り下げる分科会

- その他、音楽ライブ、ワークショップ、書籍販売/展示/交流エリアなど

※ プログラム内容は変更される場合があります。ご了承ください。

■ゲストスピーカー・講演者プロフィール

|

ロス・ジャクソン(Ross Jackson)

(グローバルエコビレッジネットワーク(GEN) 共同創始者。デンマーク環境団体 ガイアトラスト会長 デンマーク)

エコノミストであり国際的金融機関ガイアコープの会長を務めたのち、87年にガイアトラストを設立。サステナブルな社会づくりへの支援を始める。デンマークにおけるコーハウジング運動の先駆者であり、エコビレッジの世界的なネットワークづくりのためにGENの設立に寄与する。

|

|

ヒルダー・ジャクソン(Hildur Jackson)

(GEN及びガイアエデュケーション共同設立者 デンマーク)

女性運動や自然分娩、有機農法、地域社会活動など幅広い草の根運動活動家。72年デンマーク初のコウハウジングコミュニティ創設者の一人。パーマカルチャーデザイナーの資格を持ち、ラジャヨガ瞑想の教師でもある。 87年、夫のロスと共にガイアトラストを設立。93年以来、GENと共にデンマークエコビレッジネットワークの支援を進める。著書に「Ecovillage Living」等。

|

|

メイ・イースト(May East)

(ガイアエデュケーション プログラムディレクター イギリス)

30年に渡り、音楽、先住民、人間、女性、反核、環境、持続可能な定住運動などの分野で活動。1992年から英国スコットランドのエコビレッジ、フィンドホーンで生活を始める。2005年からスタートした「国連持続可能な開発のための教育の10年」の一環として、エコビレッジデザイン教育(EDE)の展開を精力的に進めている。

|

|

ヴィンヤ・S・アリヤラトネ(Dr. Vinya Ariyaratne)

(サルボダヤ・シュラマダーナ運動専務理事 スリランカ)

1958年から半世紀に渡り持続的なコミュニティ発展のために活動を展開してきた、スリランカ最大級のNGO「サルボダヤ・シュラマダーナ運動」専務理事。コロンボ大学で医学博士号、米国ジョンホプキンス大学で公衆衛生の修士号を取得。専門であるコミュニティ医療や熱帯医療の他、2004年のスマトラ沖地震被害以降の復興支援や、サルボダヤが1990年代からいち早く試行したコミュニティ開発におけるICT利用など、幅広い分野に渡る講演を多数実施。

|

|

リム・キョンス(Kyoungsoo Lim, Ph.D)

(社会貢献型企業「E-jang」創設者、最高経営責任者 韓国)

地域再生やエコビレッジ創設に関するコンサルティング事業を行う。その他、パーマカルチャー講師やソーシャルベンチャー向けアドバイザリー業務など、幅広く活動。中央政府、地方自治体、農家、NGOなど多様な組織を巻き込み、社会起業家としてエコビレッジ事業を成功させた実績を持つ。

|

|

糸長浩司(いとながこうじ)

(日本大学生物資源科学部教授、工学博士、一級建築士、パーマカルチャー・センター・ジャパン(PCCJ)代表理事)

東京工業大学大学院修了。住民参加、エコロジカルデザイン、自然建築、エコビレッジ研究をテーマに、学内や神奈川県藤野で実践的なプロジェクトも行っている。著書に「地球環境建築のすすめ」(共著、彰国社) 等。

|

|

井上昭夫(いのうえあきお)

(天理大学教授、付属おやさと研究所長、国際文化学部・地域文化研究センター長)

生態建築学に関心を持ち、NGO国境なき建築家機構(BWB)と共同で、難民人道自立支援シェルターを目的にアースバッグ(土嚢)による神戸アフガニスタン友好公園施設を構築、また地震被災地インド・グジャラート州においてボンガ(土嚢シェルター)を現地NGOらと協働建築。アフガニスタンでは、カブール大学と共同研究で将来アフガンに竹林造成を目指すプロジェクトを推進中。

|

|

辻信一(つじしんいち)

(明治学院大学国際学部教授、文化人類学者)

NGOナマケモノ倶楽部の世話人を務める他、数々のNGOやNPOに参加しながら、「スロー」や「GNH」というコンセプトを軸に環境文化運動を進める。環境文化NGO・ナマケモノ倶楽部を母体として生まれた(有)スロー、(有)カフェスロー、スローウォーターカフェ(有)、(有) ゆっくり堂などのビジネスにも取り組む。著書多数。

|

|

ピーター・デイヴィッド・ピーダーセン (Peter David Pedersen)

(株式会社イースクエア代表取締役社長)

コペンハーゲン大学文化人類学部卒業。環境経営コンサルティングやニュースキャスターを務めた後、2000年9月、CSR・環境コンサルティングを手がける株式会社イースクエアを設立。300を超える日本企業・及び行政機関のCRSコンサルティングに携わる

|

この他、総勢50名以上のスピーカーが登壇予定です

※ ゲストスピーカー・講演者は変更される場合があります。ご了承ください。

■エコビレッジ国際会議TOKYO お問い合わせ先

NPO法人ビーグッドカフェ 第3回エコビレッジ国際会議TOKYO事務局(坂本、代田)

TEL:03-5773-0225 (10:00~17:00)

ecovillage[at]begoodcafe.com

第3回エコビレッジ国際会議TOKYOは下記のご協賛企業よりサポートをいただいています。

東京建物株式会社、エコプロダクツ2009、株式会社野毛印刷社、アミタ株式会社、株式会社地球の芽

「信頼を未来へ」という企業理念のもと、東京建物はおかげさまで今年で113周年を迎えることが出来ました。私たちは総合ディベロッパーとして、地球環境に配慮した事業活動を行っています。

1)新築建物の計画における環境への取り組み

環境配慮の観点から、低負荷で省エネルギーの設備を備えるよう努め、自然エネルギーの採用や廃材のリサイクルを行っています。さらに、ご利用いただく方にゆとりある空間を提供するべく、緑化の遂行などに力を入れています。

2)既存建物のリニューアルにおける環境への取り組み

ビルの長寿命化(ロングライフ化)を図ることが出来る耐震補強は、スクラップアンドビルドが及ぼす環境負荷を減らし、また、空調をはじめとする設備の更新・効率化は、省エネルギー化に貢献します。

3)ビル運営におけるエネルギー使用量及び廃棄物リサイクルの推進

ISO14001の環境マネジメントシステムに基づく目標として、電気・ガス・水道等の使用量削減や、リサイクルを中心とした廃棄物の削減を掲げ、テナントへの啓蒙活動や各種取り組みを行っています。

4)有害物質に関する取り組み

例えば住宅に関しては、シックハウスをもたらすホルムアルデヒドや、オゾン層に影響を及ぼすフロンの影響等に配慮した部材を選定することは勿論ですが、ビルの運営においても、関連法規に基づいた有害物質の適切な保管・処理を行っています。

また、上記以外の取り組みとして、「グリーン電力証書システム」を利用し、自然エネルギーにより発電された電力(グリーン電力)を導入することでCO2排出削減に貢献しています。

東京建物は、これからも人と環境に優しいサステナブルな社会の実現を目指して参ります。

■工業用水の有効活用

|

■廃材をベンチとして再生

|

■屋上緑化

|

■太陽光パネル

|

当社は、総合環境ソリューション企業として、企業から排出される廃棄物を再資源化する「地上資源事業」、企業の環境負荷・リスク低減のコンサルティングなどの「環境ソリューション事業」、そして、地域の再生化を進める森林ノ牧場を中心とした「自然産業創出事業」の3つの事業を通して、「環境QOL」を作るリーディングカンパニーを目指して事業を行っています。

環境という市場で大きな展開をするためには、潜在的で目に見えにくい「生活の環境化」や「社会の環境化」といったニーズを捉えていく必要があります。

そこで当社はその潜在的なニーズを、関係性をもとに可視化して市場を生み出しています。今回の会議では、そうした市場創出の取り組み事例をご紹介します。

当社は、環境社会に必要となる基盤を構築し、環境生活産業を社会と共同して創出していきます。

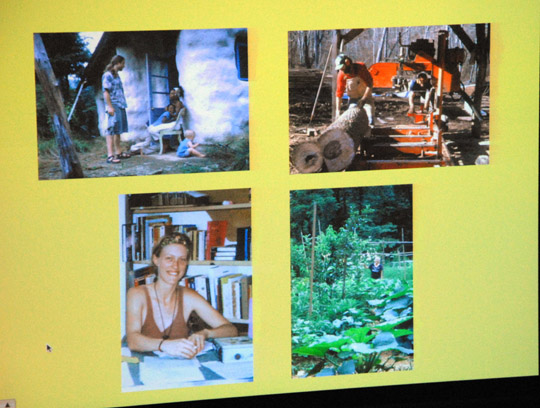

2000年に始まったエコ村構想。この自然豊かな地球で、ずっと暮らしていけるように暮らしかたを見直そう。人も、あらゆるいきものも、いきいきと暮らせる社会をつくろう。そんな思いを持った人々が集まった非営利法人が誕生し、その後、具体的なまちづくりプロジェクトが始まりました。地球の芽は、このプロジェクトの事業会社として企画開発を進めるとともに、まちの人達と未来の暮らしづくりを行っています。活動のキーワードは、自覚・主体性・コミュニティと、グローバル・ネットワークです。

1)不動産の企画開発・販売

人と人、人と自然をつなぐ心地よいまちづくりを通じて、持続可能な暮らしのための場・人をプロデュースします。

2)調査・研究

国内外の研究者と共に、21世紀にふさわしい、持続可能なライフスタイルに関する調査・研究を行います。

3)イベントやセミナーの企画・運営

体験学習型のイベントやセミナーを通して、私たちが目指すライフスタイルを発信します。

■小舟木エコ村の遠景

|

■区画図

|

■雨水の利用

|

■住宅

|

3日間で総勢50名以上が登壇、53のプログラムを開催する「笑顔がつながる暮らし方」の一大祭典には、多くの著名人も注目。以下のみなさまに応援メッセージをいただいたのでご紹介します。

いとうせいこうさん(作家・クリエーター)

|

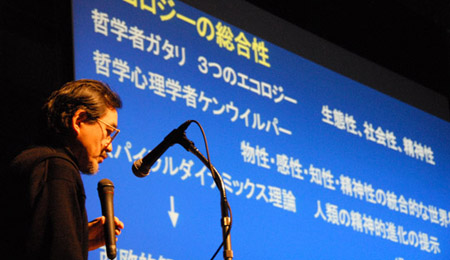

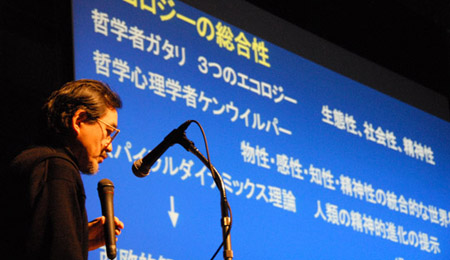

故フェリックス・ガタリはこう言った。

「大気汚染や、温室化作用による地球の温暖化に対する答えは、ものの考え方の変化や新しい生き方の技術の登場なしには考えることはできないのです」エコビレッジ国際会議もまた、新しい生き方のために存在するのだと思う。

|

Yaeさん(半農半歌手)

|

あなたにとって大切なものは何ですか?と聞かれたら。「食べること。」って真っ先に答える。それから「家族との時間」もこの上ない幸せを感じる瞬間だ。人として忘れてはいけない、いくつもの宝物を取り戻すために。もっともっとエコビレッジを世界に広げよう!

|

辻信一さん(環境運動家、文化人類学者、『カルチャー・クリエイティブ』著者)

|

世界的な「危機」の深まりの中で、巨大化した「問題」が山積していく。その一方、世界のあちこちで淡々と「答え」を生きる人々の群れが増えている。それは新しい社会の芽生えであり、それを支える新しい文化の創造だ。そんな文化創造者(カルチャー・クリエイティブ)たちに出会い、連なるために、

あなたもエコビレッジ国際会議へ。

|

枝廣淳子さん(環境ジャーナリスト)

|

温暖化をはじめとする地球環境問題はグローバルだけど、環境問題と自分とのつながりはいつも、自分の住まいや食べ物、地域や自然との関わり、そして、自分の心の中の思いや気づきがベースとなります。一歩ずつ、ゆっくりと、自分の腑に落ちているかを確かめつつ、決して絶望することなく、光に向かって歩いていきましょう。

|

ダイアナ・クリスティアンさん

(第2回エコビレッジ国際会議TOKYOゲスト、Ecovillages newsletter編集長、「Creating a Life Together」「Finding Community」著者)

|

今回のエコビレッジ国際会議TOKYOもとにかくお勧めです。参加者はきっと多くの刺激と感動を感じ、この輝かしいイベントで得たものが、未来への勇気をあたえてくれるはず。私も光栄なことに前回ゲストとして参加しましたが、53プログラムに拡大した今回の国際会議はさらに素晴らしい内容になるでしょう。

海外からのスピーカーは私もよく知っていますが、エコビレッジムーブメントの中で国際的に名高い方ばかり。私もぜひ参加して彼らから学びたかった!もし、あなたが幸運にも日本に住んでいて、この素晴らしい世界的イベントに参加できるなら、ぜひ参加してください。必ず多くのことを得られるはずです。

www.ecovillagenews.org

www.DianaLeafeChristian.org

|

I cannot recommend the Ecovillage Conference Tokyo 2009 highly enough. I believe that conference participants will feel personally inspired and uplifted — and encouraged for our global future by what learn at this brilliant event — even more so than at the wonderful Ecovillage Conference Tokyo 2007, which I had the honor to attend. I am especially familiar with the work of the overseas keynote speakers at the upcoming 2009 Conference, all renowned international figures in the ecovillage movement — Ross and Hildur Jackson from Denmark, who were instrumental in founding the Global Ecovillage Movement (GEN); May East of Findhorn Ecovillage, who helped involve the UN’s CIFAL program in the ecovillage movement; and Dr. Vinya Ariyaratne, director of the breathtakingly effective Sarvodaya Shramadana movement in Sri Lanka. Ah, how I wish I could attend and learn from these and the other keynote speakers, and attend some of the conference’s 53 workshops! If you are fortunate enough to live in Japan and can arrange to attend this seminal worldwide ecovillage event, please do! You’ll be so glad you did!

—Diana Leafe Christian, publisher, Ecovillages newsletter, and author, Creating a Life Together: Practical Tools to Grow Ecovillages and Intentional Communities, and Finding Community: How to Join an Ecovillage or Intentional Community

持続可能な暮らし方に取り組む、25団体40名以上が登壇、 3日間で50以上のプログラムを開催する一大祭典、「エコビレッジ国際会議TOKYO」を一緒に創りあげるボランティアスタッフを大募集します。事前〜当日までさまざまなタイプの活動があります。スローで多彩な仲間たちとつながる機会。ぜひご参加ください!

■事前ボランティア、まだまだ大募集!

開催まであと数日となりました! 直前のボランティアスタッフを大募集します。1日1時間からご参加が可能です。広報活動やスタッフパス、展示づくりなど、みんなで楽しみながらイベントをつくっていきましょう!

参加希望の方は、ページ下のお問合せアドレスまで参加可能枠をお知らせください。

4月22日(水)

第1集合時間 10:00~ BeGood Cafe事務所

第2集合時間 13:30~ BeGood Cafe事務所

第3集合時間 19:00~ BeGood Cafe事務所

4月23日(木)

第1集合時間 10:00~ BeGood Cafe事務所

第2集合時間 13:30~ BeGood Cafe事務所

第3集合時間 18:30~ GEIC (地図はこちら)

■当日ボランティアについて

→ご応募多数につき締め切らせていただきました。ご協力ありがとうございます!

日時: 2009年4月24日(金)~ 26日(日)

場所: 東京都渋谷区(東京ウィメンズプラザ、国連大学他)

人数: 約30名

-オーガニックランチをご用意します(昼・夜の2食)

-1日単位でご応募可能です (各日8:30-21:30)

内容: 会場設営/撤収、受付、チケット販売、会場管理(誘導等)

ゲストケア、スタッフケア、ステージ運営、記録など

■ボランティアのお楽しみ、打ちあげカフェ&上映会も開催

「ボランティアもやってみたいけど、プログラムもちゃんと見たい」という方に朗報!!

ボランティアさん限定の打ちあげカフェ&上映会を開催します!

・5/10 (日) 都内を予定 定員50名

※詳細はボランティア専用MLにてお知らせいたします。

■お申し込み、お問合せ

ev_staff※begoodcafe.com(※を@に変えてください)

TEL: 03-5773-0225(平日10:00~18:00、担当: 平野、坂本、代田)

ボランティア応募の方は、下記情報をご記入ください。

1)参加可能日、2)お名前、3)当日の連絡先(携帯など)、

4)語学レベル(英語/自己申告)5)簡単な自己紹介、メッセージなど

◎エコビレッジ国際会議TOKYOの詳細はコチラ

→ http://begoodcafe.com/archive-bgc/ecvc2009

全般

Q.「エコビレッジ」って何ですか?

エコビレッジとは、気候温暖化やエネルギー問題、食の安全、農村や里山の再生など、現代社会が直面する様々な問題に対し、ライフスタイルの各面で持続可能な解決策が実践されているコミュニティや地域の総称です。温かみのある人間関係を取り戻し、地球に負荷をかけない新しい暮らし方として、都市・農村を問わず世界中に広まっています。

Q.初めてですが、1人で参加しても大丈夫ですか?

はい!ぜひご参加ください。1人で参加される方はたくさんいらっしゃいますし、交流カフェやワークショップなど、参加者同士が交流できる仕掛けもありますので、ご心配は無用です。

Q.チケットが高いです・・・。

海外から複数のゲストを招聘する関係で、通常のBeGood Cafeのイベントよりチケットが高めになっています。来場者の皆様のご期待に沿えるよう、スタッフ一同準備に尽力しておりますので、ぜひご来場ください。

※当国際会議は収益を目的とした事業ではありません。開催後、事業収支をウェブにて公開いたします。

Q.エコビレッジに興味はありますが、まだよく知らないので、どのプログラムに参加していいかわかりません。オススメはありますか?

●まずは、基調講演やグランドディスカッションで全体感をつかんでみてはいかがでしょうか?

24日(金)

プログラム01:基調講演「環境危機世紀 持続可能なコミュニティへの挑戦」

プログラム08:ディスカッション「エコビレッジムーブメント 〜世界的潮流を俯瞰する」

●ワークショップ形式でわいわい学んでみるのもオススメです。

25日(土)

プログラム20:みんなで語ろう・つながろう「エコビレッジって何?」

●映像で見るとイメージし易いかもしれません。海外のエコビレッジや、日本の都心にあるコーポラティブ住宅の事例などを映像で紹介しています。

25日(土)

プログラム15:上映会「パーマカルチャー 〜ニュージーランド虹の谷の農園から」「かんかん森の木のはなし」

Q.英語が苦手ですが、大丈夫ですか?

はい。海外ゲストによる講演やディスカッションには日本語通訳がつきますので、ご安心ください。

Q.せっかくなのでスタッフとして関わりたいのですが。

ありがとうございます!当日のボランティアスタッフは定員のため締め切りましたが、開催前の「チラシ配布ウォーク」など事前準備を手伝ってくださる方を募集しています。一緒に国際会議を盛り上げましょう!

詳細はこちら http://begoodcafe.com/archive-bgc/ecv2009_volunteer

Q.過去2回参加しています。今回は何が違いますか?

2回のご参加ありがとうございます!今回のポイントは、「豊富な国内事例」「つながりの仕組み」の2点です。

過去2回の開催を通じて、エコビレッジの考え方に共感してくださる方が日本各地に増え、実際に行動を起こしている方も多くいらっしゃいます。今回はそういった実践者達に多数お集まりいただき、それぞれの取り組みを報告・共有していただく予定です。

また、そういった各地の取り組みを「つなげる」ため、開催期間を3日間に拡大し、ディスカッションやワークショップなど参加型のプログラムを充実させました。

日本でも続々と新しい取り組みが始まっています。実践者達のエネルギーをもらいに、ぜひ会場にお越しください。

チケット購入について

Q. チケットの買い方がよくわかりません。

まずは、こちらのページをご覧ください。

http://begoodcafe.com/archive-bgc/ecvc2009_ticket

それでもやっぱりわからない!という場合は、以下にお問い合わせください。

NPO法人ビーグッドカフェ 担当:坂本、代田

TEL: 03-3794-2302(平日10:00-18:00) ecovillage[at]begoodcafe.com

Q.行けるかどうか直前までわかりません。チケットは当日でも買えますか?

はい。会場で当日券を販売しています。(前売り券は4月22日までの販売)

Q. 領収書は発行できますか?

はい。ローソンチケットをお持ちのうえ、当日会場受付でお申し出ください。スタッフが対応いたします。

会場、会期中について

Q.青山エリアはあまり知らないのですが、お昼を食べる場所はありますか?

はい。会場周辺には、カフェやレストランがたくさんあります。

また、ベジタリアンの方も安心して召し上がれるオーガニックランチボックスを会場にて販売する予定です。

完全予約制ですので、お早めにお申込みください。

予約期間:4/3(金)〜4/17(金) 販売価格:800円

申し込み:下記事項を明記の上メールでご注文ください。各開催日(11:30〜14:00)に会場現地にてお渡しします。

1)申し込み日付(日付の後に×を記載) 24日 25 日 26日

2)数量(日付の後に数を記載) 24日 25日 26日

3)お名前 4)メールアドレス

申し込み、問合せ先:

info※peacedeli.com(※を@に変えてください) /TEL: 03-6794-8819(平日10:00〜18:00、担当:新納)

http://peacedeli.com/

Q.途中で入退場は可能ですか?

はい。来場者の皆様には、入場証をお渡しします。出入りの際に会場スタッフにご提示いただければ、自由に出入りが可能です。

Q. 託児所はありますか?子供と一緒に参加できますか?

はい。ウィメンズプラザに託児室があり、一部の時間帯でご利用になれます。(利用可能時間: 24日終日、25日午後及び夜間、26日午前)利用をご希望の方は、4/12までに事務局までご連絡ください。

Q. 地方から参加します。近くに宿泊場所はありますか?

はい。会場の青山・表参道周辺にはたくさんのホテルがあります。

ホテル検索 http://www.jalan.net/

また、会場から地下鉄で2駅の場所にリーズナブルなユースホステルもあります。

http://www.jyh.gr.jp/yoyogi/index.html

by Diana Leafe Christian

Penny’s and my favorite conference presenter was Professor Yasuhiro Endoh of Aichi Sangyo University in Nagano. An older man in perhaps his early 60s with an amiable expression and an unmistakable air of warmth and friendliness, Professor Endoh travels the length of Japan advocating “collective housing” through his nonprofit, “Team of Green Growth.” He showed slides of a successful 22-year-old collective housing development in Kyoto, “U Court.” The project, completed in 1985, consists of 48 units in three buildings of from three to five stories each. The buildings are arranged around a south-facing “U”-shaped courtyard surrounding tall trees and a patio. U-Court doesn’t have a common kitchen/dining room. However, with a shared meeting hall, all stairwell entries facing into the courtyard so people meet their neighbors daily, open and shared ivy-covered balconies that serve as outdoor hallways running along the courtyard side of the buildings, and parking out of sight in one corner of the property, it sure seemed like “proto-cohousing” to me.

Professor Endoh emphasized the importance of trees and the natural environment in creating community. U-Court residents debated whether to plant trees in their central courtyard, which would have been expensive for them, but finally did plant trees. The presence of these trees later made all the difference in cooling the building, adding a beautiful, shady outdoor place for neighbors to gather in spontaneous as well as planned meetings, picnics, and celebrations. U-Court residents also all grew ivy up the sides of the buildings and especially across their shared balconies. At first they couldn’t get flowers and shrubs started along courtyard walkways because their toddlers would gleefully rip them out. So U-Court parents waited until the children were slightly older and asked them to plant flowers and shrubs and water them. The kids leapt into the project and proudly cared for the landscaping for years, later noting how important it had been to them return from school everyday and feel welcomed home by natural beauty. The parents also considered building a small round pond for the children to wade and splash in. While some were concerned it would be unsafe, they finally did build a pond, and it became the centerpiece of the children’s experience of the courtyard as they grew up. “You can’t believe the happy memories people who’d grown up at U Court had when they came home from school only to find that one of the men had gotten drunk and fallen into the pond again,” Professor Endoh explained, showing a photo of a man half-lying in a shallow pool, submerged up to his armpits, a silly grin on his face. Nature, ponds, and water are so important to Japanese people that one pair of neighbors created a small fishpond on their shared balcony and stocked it with koi.

Professor Endoh’s longitudinal study of the of young adults who’d grown up at U-Court indicated that they had loved the natural environment there and their sense of safety and connection to so many adults who served as substitute aunties and uncles. Like kids raised in community anywhere, they were much more confident and socially developed than their counterparts who’d grown up in conventional housing. And, not surprisingly, they wanted to move back to U-Court to raise their own children there too.

by Diana Leafe Christian (for Cohousing Journal online, February, 2008)

After the Japanese Ecovillage Conference in Tokyo in late November, 2007, I and one the conference hosts, Akemi Miyauchi, visited three “collective housing” projects in Tokyo. At the conference I first heard this term for high-density housing projects with various kinds of common space—but it sure sounded like cohousing to me!

A few days after touring Kankanmori no Kaze Cohousing (See Part I in the February, 2008 issue), Akemi and I visited developer Tetsuro Kai, who at the ecovillage conference had described three beautifully designed and landscaped “collective housing” projects. We met in his offices at one of his projects: the 12-unit Kyodo no Mori (“Forest of Kyodo”) in the Setagawa district of Tokyo. Kyodo no Mori is three-story building on a tiny, fifth-acre lot, with vine-covered balconies, passive solar heating and cooling, solar-powered water pumping, and a constructed wetlands for greywater treatment on a rooftop terrace. Units average at about 970 sq. ft. Unlike Kankanmori, most units are not rented but owned by Kyodo no Mori’s residents. Common house features were not included in the building, however residents have shared outdoor space in a ground-floor courtyard, small second-floor terrace, and rooftop garden, which has a small barbeque grill surrounded by built-in seating for cook-outs. Completed in 2000, this project was described as Japan’s first cohousing community in Graham Meltzer’s 2005 book, Sustainable Communities.

Mr. Kai, a charming and gracious host, seemed inspired and passionate about his collective housing projects, and the participatory design process he developed for them. He and the architect met with future residents of Kyodo no Mori to learn what they’d ideally like in their individual apartments. He and the architect met first with individual households, then in small groups of several households, and lastly as a whole group. A problem for concern for any one household was considered an issue for the whole community, and solutions were applied to all residences. Mr. Kai realized that this process would not only help the project to better serve the needs of its future residents, but would also help create a sense of community before everyone moved in. Although similar to the participatory process used by the Danish architects who developed cohousing in the 1960s, Mr. Kai’s method is not based on the cohousing process and was created independently.

Mr. Kai also told us about the 15-unit Keyaki House project, completed in 2003, which we were about to see. The original owner of the __-acre property had a one-story traditional Japanese house and a relatively large garden. To reduce future inheritance taxes for his heirs, the owner sold part of the property to Mr. Kai for high-density housing development. Because Tokyo needs more housing, they reward urban landowners who sell their property for this purpose with inheritance tax breaks. The owner didn’t want to leave the site and so built a new two-story house for himself on the part of the property he retained. Mr. Kai suggested a win-win arrangement in which his traditional one-story house became the meeting hall and common space for Keyaki House residents and himself, who together form a small community. Everyone shares the garden courtyard formed between the three buildings.

The owner’s favorite tree, which he had climbed as a boy, is an 80-foot Japanese Zelkova tree (Keyaki in Japanese). But it was in the wrong location for the site plan to work, so Mr. Kai’s company dug up the huge tree and moved it 30 feet!

We saw a scale model of Mr. Kai’s newest project, Kaze no Mori (“Wind in the Forest”), which has the same kind of site-use arrangement as Keyaki House with the original property owner. Like Kyodo no Mori, most residents of Kaze no Mori and Keyaki House had input into the design of their units via the participatory design process, and meet regularly to make community decisions.

When we arrived at Keyaki House, a short distance away, we saw the magnificent Keyaki tree, with a trunk diameter of about three feet. It was truly the centerpiece of the courtyard, nestled in the inner corner of the L-shaped building, with a network of lacy-looking open-mesh metal stairways and walkways curving around it. Next to the base of the Keyaki tree and under the overhead walkways was an enchanting sight—a Japanese-style fishpond with large stepping stones leading across to the stairway and elevator leading to the apartments above. Before you encounter concrete, metal, and high-technology, you move through a beautiful natural environment. On the second floor landing Mr. Kai pointed out how moveable screens of closely spaced wooden lattice strips on the outside “wall” of each unit’s wide balcony create a privacy gradient between each apartment and the wide curving metal walkways, which also serve as common space. We saw the rooftop vegetable garden on the four-story wing, and the tiny grassy park on the roof of the five-story wing, where in summer community children sometimes put up tents and camp out.

The traditional Japanese love of nature, gardens, and especially forests and trees, was quite evident in the projects I visited as well as in similar projects described at the conference. I saw this only in their vine-covered trellised balconies and tree-filled courtyards, but also in evocative names such as “and “Forest of Kyodo” and “Wind in the Forest. (And the name of the cohousing project we’d visited earlier, Kankanmori no Kaze, means “Winds of Kankanmori Forest.” )

What the projects I visited have in common are residents who had input into the design, hold community meetings, and live in projects in which the site plan and shared common space help induce a sense of community. However, Kankanmori has the same kinds of common house amenities as you’ll find in any cohousing community in North America, but the other projects have minimal common space. And perhaps because Kankanmori has slightly smaller units and looked like any concrete high-rise anywhere, it seemed more affordable. Mr. Kai’s three projects seemed more upscale because of the somewhat larger units and the level of beauty and attention to detail in design and landscaping.

While Japanese people seem to love using English terms for concepts arising in the West (like “bioregional” and “ecovillage”), I wondered why the term for these communities in Japanese is “collective housing” rather than the English word “cohousing.” However, Hiroko Kimura, founder of Kankanmori, did describe the project as “Tokyo Cohousing” when she presented at the first Japanese Ecovillage Conference in 2006.

Also, while in any cohousing community tour in North America people are routinely invited into homes to see the interiors of a typical units, I got the impression that this will not happen in Japan because of significant cultural differences—the important distinction made between the “public face” and “private face” in Japan, and the fact that in Japan one’s home is an exceptionally private place. Hence, as gracious as our hosts were, we were shown only the courtyard and rooftops of Keyaki House, the courtyard and Mr. Kai’s offices at Kyodo no Mori, and the interior common spaces and rooftop terraces at Kankanmori.

Given the tendency in Japan to adopt and master useful innovations, I wouldn’t be surprised if cohousing takes off in a big way in this country. Perhaps in the not-too-distant future we’ll be meeting at an international cohousing conference . . . in Kyoto!

Diana Leafe Christian is editor of a free online ecovillage newsletter, “Ecovillages and Sustainable Communities.” (Diana@ic.org). Author of Finding Community: How to Join an Ecovillage or Intentional Community, and Creating a Life Together: Practical Tools to Grow Ecovillages and Intentional Communities, she was editor of Communities magazine for 14 years. Diana lives at Earthaven Ecovillage in North Carolina. www.DianaLeafeChristian.org

DianaLeafeChristian.org

by Diana Leafe Christian (for Cohousing Journal online, February, 2008)

As cohousing is increasingly becoming a global phenomenon, I’ve become curious to learn how different countries mold the concept to reflect their cultural, financial, and regulatory realities. I learned that firsthand after I had a chance to see three cohousing projects in Japan recently.

After the Japanese Ecovillage Conference in Tokyo in late November, 2007, three of us visited the 28-unit Kankanmori no Kaze Cohousing project in Tokyo. My two friends were Giovanni Ciarlo from Huehuecoyotl Ecovillage in Mexico, and Akemi Miyauchi, one of our wonderful conference hosts. Giovanni and I had given presentations about intentional communities at the conference, and we were eager to see similar projects in Japan. There appear to be relatively few intentional communities in that island nation, and perhaps only four cohousing communities so far—depending on how one defines the term.

We first learned of Kankanmori at the conference through presentations on what the Japanese call “collective housing” in Sweden, Denmark, the US, and Japan. I was quite surprised to learn that the first example one conference presenter could find of collective housing in modern times was in Sweden before World War II, where single mothers organized shared apartment buildings with common kitchen/dining rooms and shared childcare.

Kankanmori no Kaze (which means “The Winds of Kankanmori Forest”) is located in the 12-story Nippori Community House in the Arakawa section of Tokyo. The second and third floors contain the apartment units, common spaces, and rooftop terraces of the multi-generational Kankanmori Cohousing. However, the other floors are not part of the cohousing project: the ground floor is a restaurant, a nursery school, and a medical services station staffed by nurses for residents and neighbors, the higher floors contain a nursing home and independent-living apartments for mobile seniors, and the top floor offers furo bath facilities all residents can use.

Kankanmori differs from most cohousing projects in the West in that it is entirely rental units. The studio and two-bedroom units (no one-bedroom units), which range from 270 to 645 sq. feet, rent for between approximately $640 to $1550 a month, plus about $65 a month for each unit’s share of utilities for the common spaces. The Kankanmori project was considered quite an experiment, as its future residents gave their input into the design, and provide the cleaning and maintenance of the common spaces—unusual for Japan.

Giovanni, Akemi, and I entered Kankanmori through an outdoor stairway to the second floor entrance, where we met architect and project founder Hiroko Kimura, who gave us a tour of the common facilities. On the first cohousing floor we saw the common kitchen and pantry, which looked like every common house kitchen I’ve ever seen but for the row of rice cookers, a bamboo vegetable steamer, and Japanese rather than English on the labels of every package, bottle, and can. We toured the spacious dining room, the small living room off the dining room, and the outdoor dining terrace with a living “wall” of trellised vines on the balcony. We visited the children’s play area, bathroom, laundry and ironing rooms, the indoor/outdoor woodworking/crafts terrace, and the flower garden and vegetable garden terraces. Located on the roof of the first floor, the gardens had deep raised garden beds in wooden frames, wooden walkways, and rows of plastic compost bins. On the next floor of the cohousing complex we saw the group’s office, library shelves, woodworking shop, and guest room.

Located on the roof, the flower garden and vegetable garden terraces had deep raised beds in wooden frames, wooden walkways and rows of plastic compost bins. The Japanese had an ancient, even sacred, sense of connection to nature, especially trees and forests. (They’ve preserved 66% of their island nation in forest, which is impressive, given the pressure to cut forests to get more arable land to feed a population of 127 million.) But nowadays most Japanese in urban areas live in small box-like apartments in concrete high-rises, with little connection to neighbors or nature. Land is so expensive that few housing developers include gardens or landscaping. So Kankanmori’s connection to neighbors and to nature once again is quite exceptional.

Ms. Kimura also showed us the community’s bulletin-board systems for cooking and cleaning schedules and using the laundry facilities, and described how they worked. People write their names on small brightly colored circular magnets, which they place on a large wall calendar on the dates on which they’d like to cook and clean. In the laundry room they affix small paper tags to their washer or dryer they’re using to let the next person know how to dry their wet loads or where to put their dried loads before they put in their own. Ms. Kimura also described community meetings, and told us that when residents have differences, “We just talk together until we can come to agreement about what to do.”

The most moving part of the tour, for me, was that while I was 5,000 miles from North America, visiting a culture significantly different from my own, the common spaces and description of Kankanmori’s cooking rotation, laundry use, and interpersonal process were so familiar. Giovanni and I told Ms. Kimura that the kinds of conflicts and topics she described in their meetings also came up at Huehuecoyotl and Earthaven as well. Whether in Mexico, Japan, or North Carolina, communitarians seem to evoke the same set of living-together issues!

Before we left Kankanmori, Ms. Kimura invited us to participate in one of their common meals the next time we came to Tokyo. We said we’d love to!

Part II will examine two additional high-density housing projects in Tokyo that combine individual units with unusual methods for creating common space.

Diana Leafe Christian is editor of a free online ecovillage newsletter, “Ecovillages and Sustainable Communities.” (Diana@ic.org).

Author of Finding Community: How to Join an Ecovillage or Intentional Community, and Creating a Life Together: Practical Tools to Grow Ecovillages and Intentional Communities, she was editor of Communities magazine for 14 years.

Diana lives at Earthaven Ecovillage in North Carolina.

DianaLeafeChristian.org

By Giovanni Ciarlo, Diana Leafe Christian

The 2007 International Ecovillage Conference was held in Tokyo, Japan, November 23-24, 2007 with a packed crowd of Japanese environmental activists, progressive university professors, enthusiastic students, and the “green press” in Japan. The second such event held in Tokyo, the conference was hosted by BeGood Cafe and the Permaculture Center of Japan, two nonprofits dedicated to promoting ecological sustainability throughout the country.

The conference was kicked off by Koji Itonaga, Professor of Biosource Sciences at Nihon University and conference co-host, who urged Japan, among other tasks, to protect and revitalize its remaining 135,000 villages through permaculture design and ecovillage projects, ecologically sustainable housing, bioregionalism, and eco-tourism. Yasuhiro Endo, Professor at Aichi Sangyo University, called for more collective housing projects in Japanese cities, showcasing the very successful “U-Court” collective housing project in Kyoto, to much laughter and applause. Ms. Ikuko Koyabe, Professor at Japan Women’s University and author of Let’s Live in a Collective House, presented case studies of collective houses in Sweden, Denmark, and the US, and how this has been translated to collective housing in Japan, especially in the Kankanmori collective housing project in Tokyo. Other Japanese presenters described collective housing communities in Tokyo, ecovillages in Denmark, a Japanese aid project providing wind generators to communities in East Africa, sustainable forestry and building with wood products to create better home environments and revive the economy of Japan’s mountain villages, and plans to revitalize Japanese villages in the Goshima Islands and Hokkaido Date city, respectively.

Overseas guests presented as well. Diana Leafe Christian, author of Finding Community and Creating a Life Together, former editor of Communities magazine, and editor of the new online ecovillage newsletter, Ecovillages and Sustainable Communities, introduced the ecovillage concept with examples worldwide. In a second presentation she focused specifically on the ecologically and financially sustainable aspects of three projects: Earthaven in North Carolina (where she lives), Findhorn Foundation in Scotland, and Kommune Niederkaufungen in Germany.

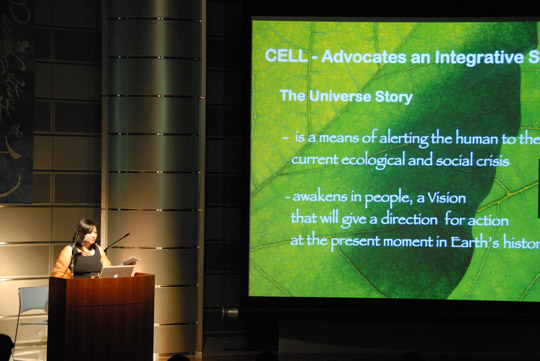

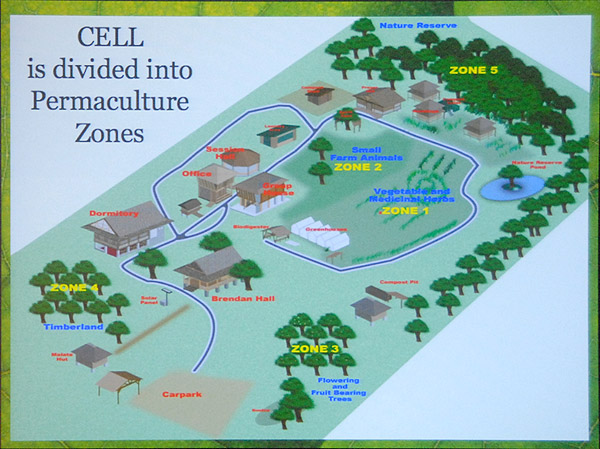

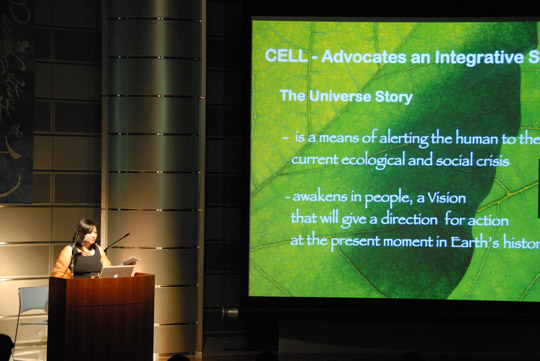

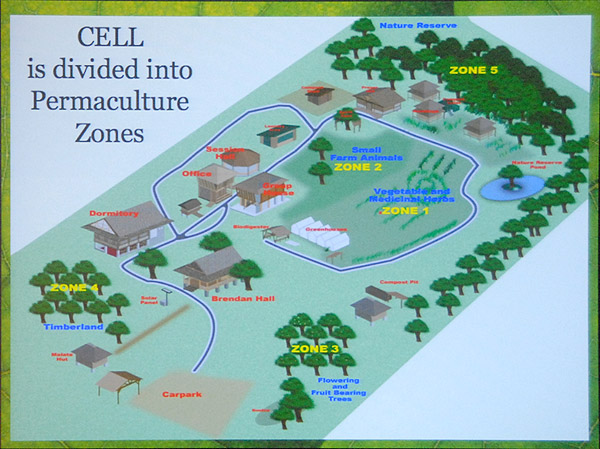

Environmental scholar Penny Velasco, director of the GEN-Oceania/Asia in the Philippines, directing manager of Earth Day in the Philippines, and author of Are You the Forest King?, described how a new ecovillage project, Pintig Cabio in Manila, is being cofounded by three nonprofits: Happy Earth, which produces environmental education materials; The Center for Ecozoic Living and Learning (CELL), a Creation Spirituality-oriented environmental education center; and the Cabiokid Foundation, a fully developed permaculture demonstration site immediately adjacent to the ecovillage site. Giovanni Ciarlo, cofounder of Huehuecoyotl

Ecovillage in Mexico, representative from Mexico to the Ecovillage Network of the Americas (ENA), and member of the Board of Directors of the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN), gave a presentation about ecovillage projects in Latin America, including

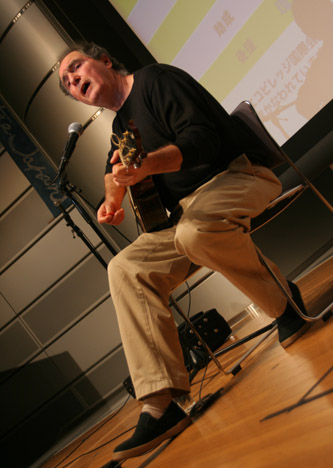

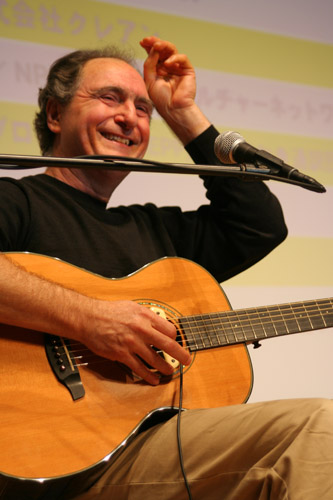

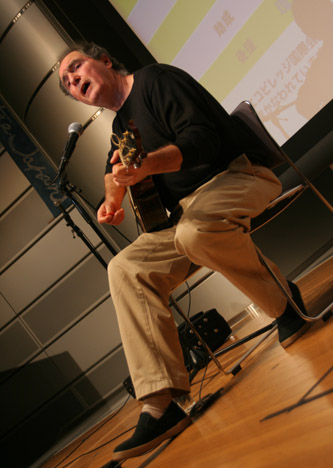

Huehuecoyotl and Las Cañadas in Mexico, Sasardí Nature Reserve in Colombia, IPEC and ABRA 144 in Brazil. Giovanni also played guitar and sang, getting the crowd clapping and singing along to songs, including his original songs, in Spanish. Kyle Holtzetar, an American Ph.D. student at Nihon University, described the ecologically sustainable aspects of Camphill Kimberton Hills community in the U.S.

The ecovillage conference was also blessed by an unexpected visit by renowned sustainability activist Helena Norberg-Hodge. Founder and director of the International Society for Ecology and Culture, co-founder of the International Forum on Globalization, director of the Ladakh Project, author of Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh,

recipient of the Right Livelihood Award, and longtime GEN activist, Helena, in Japan on other business, stopped by the ecovillage conference to help encourage ecovillage activism in Japan. She also described her new video project about measuring a country’s progress in terms of its happiness levels.

Professor Yasuhiro Endoh of Aichi Sangyo University in Nagano showed slides of U- Court, a successful 22-year-old collective housing development in Kyoto. The project, completed in 1985, consists of 48 units in three buildings, each three to five stories tall. The buildings are arranged around a south-facing U-shaped courtyard containing tall trees and a patio. U-Court doesn’t have a common kitchen or dining room, but in many ways it resembled cohousing. It boasts a shared meeting hall, stairwell entries that face into the courtyard, shared ivy-covered balconies running like outdoor hallways along the courtyard sides of the buildings, and hidden parking in one corner of the property.

At the end of each day the presenters took part in a panel discussion moderated by Koji Itonaga, Professor in the College of Bioresource Science at Nihon University.

The conference was widely reported on through print media by Bio-City magazine editor Hiroki Sugita as well as by Yukihiro Noda of the The conference was widely reported on through print media by Bio-City magazine editor Hiroki Sugita as well as by Yukihiro Noda of the television program “Green-Power TV,” who will post a video of interviews and conference highlights in January at www.green-power.tv

Official conference sponsors included Bio City magazine, several Japanese sustainability-oriented corporations, and the Japanese Ministries of the Environment and of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. Emcees were Jun Shikata of BeGood Cafe and Koji Itonaga.

The first International Ecovillage Conference in Japan was held in October, 2006 in Tokyo. Overseas guests were Lois Arkin of Los Angeles Eco-Village and West US representative to ENA, Liz Walker of EcoVillage at Ithaca in New York state and co-creator of GEN’s EDE program, Max Lindegger of Crystal Waters in Australia and director of GEN-Oceania/Asia, and Marti Mueller of Auroville community in India.

CONTACT:

BeGood Cafe: begoodcafe.com, Contact Form

Diana Leafe Christian: DianaLeafeChristian.org, diana@ic.org

Penny Velasco: happyearth.info, penny@happyearth.info

ena.ecovillage.org

gen.ecovillage.org

Giovanni Ciarlo: sircoyote@aol.com

– Ecovillage Network: http://www.ecovillage.org

– Ecoaldea Huehuecoyotl: http://www.huehuecoyotl.net

By Diana Leafe Christian

The Japanese audience was singing along with ecovillager Giovanni Ciarlo—in Spanish! It was the second International Ecovillage Conference, held in Tokyo in November 2007. The packed crowd included environmental activists, progressive university professors and students, and Japan’s “green press.” Speakers included professors of architecture and engineering, innovative housing developers, environmental activists with special projects in rural areas of Japan, and three overseas guests—Giovanni, Penny Velasco, and me.

The conference was a wonderful opportunity for the three of us to learn about Japanese culture. We were told that people in Japan once had a powerfully developed sense of community and connection to neighbors, in thousands of rural villages as well as in city neighborhoods. They also had an ancient, sacred sense of connection to nature, especially trees and forests. But nowadays most Japanese in urban areas live in tiny apartments in concrete high-rises, with little connection to neighbors or nature. Land is so expensive that few apartments include gardens or landscaping. So the Japanese projects presented at the conference, while not “ecovillages” perse, were nevertheless inspiring to the audience because they made the connection with neighbors and nature once again.

They were inspiring to us overseas guests, as well—we enjoyed learning about Japanese colleagues doing projects similar to our own. For instance, Ikuko Koyabe, architect and Professor at Japan Women’s University, presented case studies of what the Japanese call “collective housing”—what we would call cohousing. She described projects in Sweden, Denmark, and the US, and then introduced us to the Kankanmori cohousing project in Tokyo.

Housing developer Akinori Sagane spoke of his work supporting the economic revitalization of remote mountain villages by encouraging sustainable forestry practices and a return to using wood as a building material.

Professor Yasuhiro Endoh of Aichi Sangyo University in Nagano showed slides of U- Court, a successful 22-year-old collective housing development in Kyoto. The project, completed in 1985, consists of 48 units in three buildings, each three to five stories tall. The buildings are arranged around a south-facing U-shaped courtyard containing tall trees and a patio. U-Court doesn’t have a common kitchen or dining room, but in many ways it resembled cohousing. It boasts a shared meeting hall, stairwell entries that face into the courtyard, shared ivy-covered balconies running like outdoor hallways along the courtyard sides of the buildings, and hidden parking in one corner of the property.

Housing developer Tetsuro Kai showed slides of two collective housing projects in Tokyo: Kyodo no Mori and Keyaki House. Each is a concrete multi-story apartment building with rooftop gardens and vine-covered vertical surfaces and balconies. The three-story Kyodo no Mori features passive solar heating and cooling, a rooftop wetlands for greywater recycling, and a solar-powered water pump. It was described as Japan’s first cohousing community in Graham Meltzer’s 2005 book, Sustainable Communities (and in the Winter 2005 issue of Communities magazine). Keyaki House is a five-story building whose residents use the original traditional house on the property as their shared common space and meeting room.

Other presenters described ecovillages in Denmark, a Japanese aid project providing wind generators to communities in East Africa, Camphill Kimberton Hills in the US, and plans to revitalize Japanese villages in the Goshima Islands and the city of Hokkaido-Date.

Giovanni, a cofounder of Huehuecoyotl Ecovillage, is Mexico’s representative to the Ecovillage Network of the Americas and a Board member of the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN). His first presentation at the conference was a slide show about successful up-and-running ecovillages in Latin America, including Huehuecoyotl and Las Cañadas in Mexico, Sasardí Nature Reserve in Colombia, and ABRA 144 in Brazil. When he played guitar and sang some of his original songs, he had everyone tapping their feet and moving to the music.

Environmental scholar Penny Velasco is director of GEN-Oceania/Asia in the Philippines and director of Happy Earth, a nonprofit that produces environmental education materials. She showed slides of Pintig Cabiao, the ecovillage she is helping to start in Manila. Pintig Cabiao is being cofounded by three Filipino nonprofits: Happy Earth; the Center for Ecozoic Living and Learning, a Creation spirituality-oriented environmental education center; and the Cabiokid Foundation, a fully developed permaculture demonstration site adjacent to the planned ecovillage site.

I gave an overview of the concept of ecovillages, with statistics from GEN, quotes from well-known ecovillage activists, and photos of Damanhur in Italy, Tlholego in South Africa, IPEC in Brazil, and Auroville in India. My second presentation focused on ecological and financial sustainability in ecovillages, highlighting Findhorn Foundation in Scotland, Kommune Niederkaufungen in Germany, and Earthaven in North Carolina, where I live.

The conference was hosted by BeGood Cafe and the Permaculture Center of Japan, two nonprofits dedicated to promoting ecological sustainability. Sponsors also included the Tokyo-based Bio City magazine, several Japanese sustainability-oriented companies, and the Japanese Ministries of the Environment and of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. On-stage hosts were Jun Shikita of BeGood Cafe and Koji Itonaga of the Permaculture Center of Japan and the College of Bioresource Sciences at Nihon University.

Giovanni, Penny, and I grew very fond of the folks at BeGood Cafe, who hosted us royally with Japanese dinners every night. The organization’s founder and director, Jun Shikita, is a former fashion industry executive who started the cafe in 1999 to share and promote practical environmental information. We were also impressed by Akemi Miyauchi, the ever-helpful, untiring coordinator, who took care of everything we needed.

After the conference the BeGood Cafe folks helped us foreign guests visit several Japanese intentional communities—a wonderful treat. Penny traveled to the Konohana Family, a 14-year-old organic farming community near Mt. Fuji. The goal of this vegetarian community, which produces nearly all its own food, is to live in harmony with the Earth and with each other. “You could feel the love among the members there,” Penny later told us.

Giovanni, Akemi, and I visited Kankanmori Cohousing in Tokyo, which is located on the second and third floors of a 12-story apartment building. We were given a tour of the common facilities by the project’s architect and founder, Ms. Hiroko Kimura. Even though we were in a culture quite different from ours, Kankanmori felt familiar—especially its common kitchen and other shared facilities, and our guide’s description of the cooking teams, common laundry use, and interpersonal process in meetings. Giovanni and I told Ms. Kimura that the kinds of topics she described in their meetings came up at Huehuecoyotl and Earthaven as well. Whether in Mexico, Japan, or North Carolina, communitarians seem to face the same kinds of issues.

Akemi and I also briefly visited Tetsuro Kai and his two beautifully designed and landscaped collective housing projects, Kyodo no Mori and Keyaki House.

I believe we in the communities movement can learn much from our Japanese colleagues—architects, developers, professors, and environmental activists like the folks at BeGood Cafe. It was an honor to meet them.

Diana Leafe Christian, author of Finding Community and Creating a Life Together and former editor of Communities magazine, is editor of the new online ecovillage newsletter, “Ecovillages and Sustainable Communities.” She lives at Earthaven Ecovillage in the US.

Contact info:

Diana Leafe Christian: dianaleafechristian.org; diana@ic.org

BeGood Cafe: begoodcafe.com/archive-bgc/main/archives/ecvc2007_report (in Japanese, with photos); Contact Form

Giovanni Ciarlo and Huehuecoyotl Ecovillage: huehuecoyotl.net; sircoyote@aol.com

Penny Velasco: happyearth.info; penny@happyearth.info

>> 3日間大盛況で終了しました!第3回エコビレッジ国際会議 レポートはこちら

>> 3日間大盛況で終了しました!第3回エコビレッジ国際会議 レポートはこちら

![]()

![]()